By Hitoishi Chakma

You have to pay a bill for using electronic money such as bKash or mPesa. In comparison you do not really have to pay to use cash. It is in your pocket and whenever you’re using it you are not paying somebody else to use it! Cash being so convenient to use – aside from it being infested with germs – it is quite a wonder that electronic money is taking off after all!

Maybe cash not having a cost is a little too convenient to be true. There must be some ways that each and every one of us is somehow paying to use cash. This is probably even more true for organisations. In our entrenched system of cash we’ve just become blind to the various costs and inefficiencies associated with it.

So, how much does it really cost to use cash? We thought this was a valid question and set about to find the answer. After initial rounds of ideas, we settled on finding blocks of similar cash transactions that happen at regular intervals and corresponding blocks of resources spent to manage them within BRAC. For this purpose we wanted to see how much an average branch (with six field agents, one manager, a fully functioning accounts department and a sizable microfinance portfolio), spends for every hundred taka that it transacts. We overlooked transactions made for other programmes since for a study as small as this, tracking those rather less regular and less comparable transactions may become too formidable to muster. What we found was interesting nevertheless!

A number of interviews and many field visits later, we were able to estimate that an average BRAC branch spends around 90 Paisa for every 100 Taka that it transacts. When you compare this with the 180 paisa that it costs for electronic money, cash wins hands down. However comparing two numbers without some context doesn’t really tell us much. You can read Toby Norman right here asking us to make quantitative comparisons more carefully. Then again quantifying or measuring something in itself is a questionable process. For a philosophical take on this you can read this amusing interview of a famous musician and a famous economist.

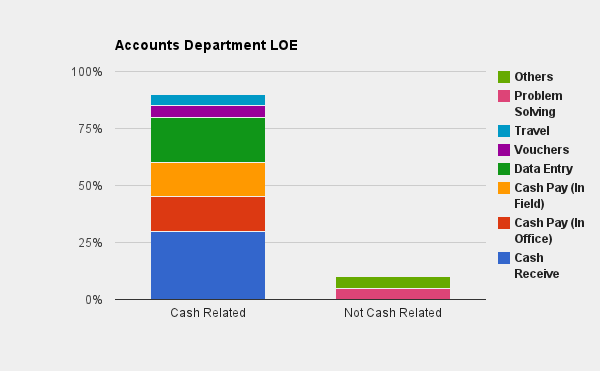

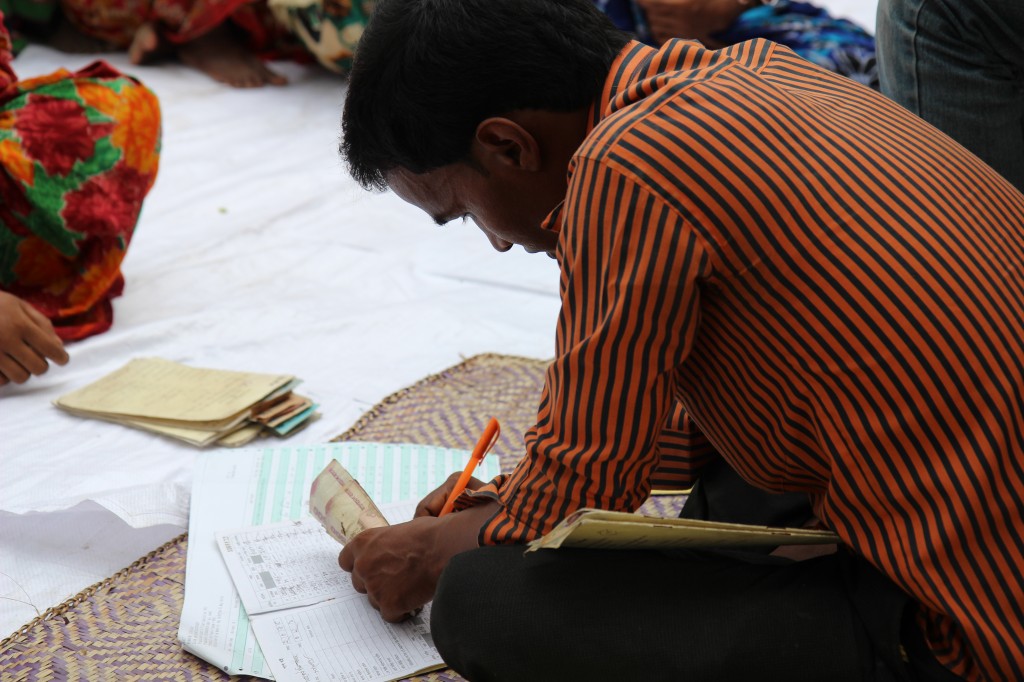

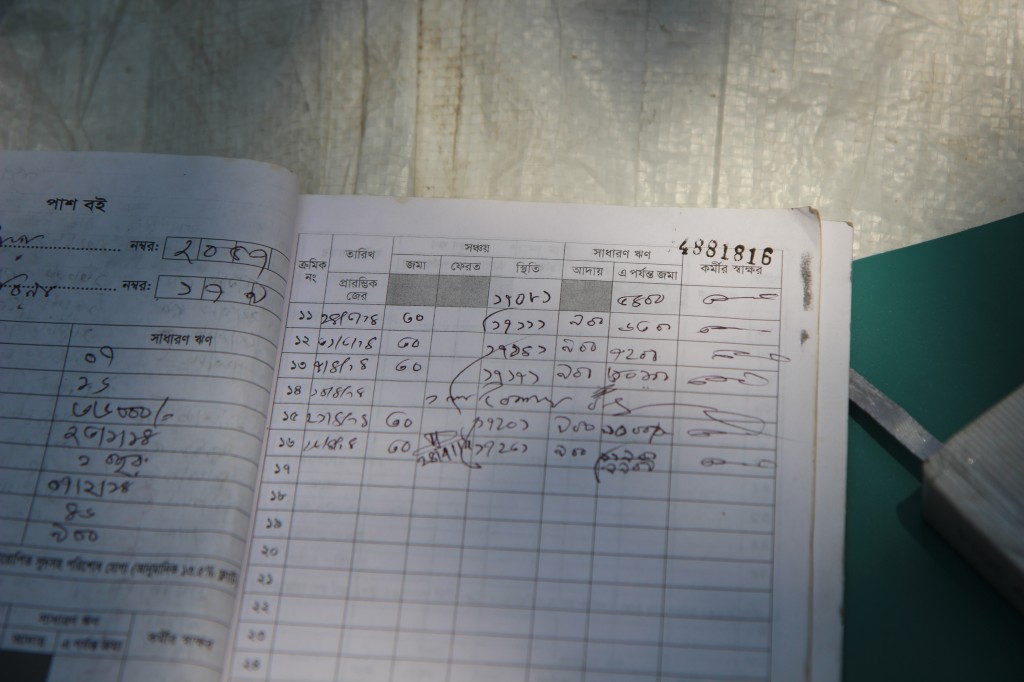

Now, what our small study confirms from the outset is that cash is not free. It is an important point to consider, as it is easy to forget. Then to render some context, our calculations took into account only the most tangible costs such as salary and equipments like computers. It did not take into account the intangibles such as wait time for the client at the branch, security concerns of carrying cash and various opportunity costs. We found that the accounts department spends around 90 percent of their time managing and documenting cash. While arguments can be made that this is what the accounts department is for, management of cash can be outsourced, and that time can be better spent serving clients. To delve a little further, when we visited a particular village organisation in Pabna in April, it happened to be the weekly market day in the middle of onion harvesting season. At the village everybody was busy picking and cleaning piles of onion drying out on their yards. What we soon realised after two hours was that to collect all the instalments, the field organiser would have to make the same forty minute trip again in the evening after everybody was back from the market, after having sold their produce. Now imagine field organisers making such trips regularly, sometimes only to collect a single instalment.

Lastly, there is the question of what is possible within the current process. If you’ve seen dominoes falling, you know the inordinate amount of labour that is put into arranging them and making sure that they follow their intended path. While they are very beautiful, they are very difficult to put up and maintain in scale. The way cash is being managed right now is quite similar. It is like an intricate and beautiful set piece that is functioning day in and day out, not without tremendous effort on the part of the various personnel associated with it. Furthermore a small deviation from the process has the potential to greatly increase the cost (e.g. missed instalment example above)– a cost that was not reflected in our calculation. And in regards to what is possible, the current process doesn’t allow us much variation in terms of service delivery, project management, monitoring, new products and services and business models. Adding more services on top of the ones that we are providing right now would not be easy to accomplish within the current framework.

Imagine that a rural woman who signs up for BRAC services three years from now is able to instantly access a multitude of services all from the doorsteps of her home, is able to make transactions with a BRAC branch 24/7, call on a Shasthya Kormi (health worker) whenever she needs her, and during emergencies she knows that she has her savings with her anywhere she goes. While transactions are ancillary to what we do, they are also an integral part of what makes our services possible. Redefining and reimagining this has the potential to upend the entire way that we think about development. Maybe it is time for such a disruption.

Hitoishi Chakma is a management professional with the BRAC Microfinance Research and Development Unit.