This post was written by Toby Norman, SIL intern and visiting researcher from Cambridge University

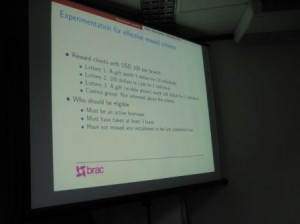

What would your program do with $100? This very real question was addressed by Dr. Munshi Sulaiman, Research Coordinator for BRAC International at the recent Innovation Forum. Given $100 per microfinance branch office in BRAC Uganda to work with, Munshi and his programme managers had a challenging question to answer. What’s the best way to reward “good” borrowers, while encouraging better performance across the whole portfolio? Focus group discussions suggested that a low-stakes raffle with prizes for 20 good borrowers was the way to go, an intuition Munshi bhai shared.

What would your program do with $100? This very real question was addressed by Dr. Munshi Sulaiman, Research Coordinator for BRAC International at the recent Innovation Forum. Given $100 per microfinance branch office in BRAC Uganda to work with, Munshi and his programme managers had a challenging question to answer. What’s the best way to reward “good” borrowers, while encouraging better performance across the whole portfolio? Focus group discussions suggested that a low-stakes raffle with prizes for 20 good borrowers was the way to go, an intuition Munshi bhai shared.

This combination of discussion and intuition is typically how decisions like this are made in programmes, not only at BRAC but at most NGOs around the world. But here Munshi bhai and his colleagues did something different, joining a growing trend in development research. They tested their intuitions through a randomized control trial, pitting the top three candidate strategies against each other with a control group in carefully chosen pilot sites. Turns out they were wrong. The hands-down winner for improving portfolio performance was actually a high-stakes raffle for a single prize, a $100 mobile for one lucky “good” borrower. News of this client’s reward spread quickly, and soon all borrowers in this group were performing better perhaps with the hopes of one day receiving their one award.

To economists the outcome of this trial—that people aren’t motivated by the lowest-risk option—may be surprising. To most psychologists this probably is not; greater motivation from high-risk, high-reward stakes is pretty well established scientifically. But what’s important here is the link between research and action. Programmes are confronted by hard decisions all the time. And they can draw up potential solutions to these problems from a number of sources: intuition, discussion, economics, psychology, and so forth. But which of these solutions is really going to work?

As a management scientist what really struck me about Munshi bhai’s presentation wasn’t the novelty of RCTs or his impressive confidence intervals. It was how he made research useful and actionable to real-world programmatic challenges. He’s a “manager’s kind of researcher”. Dare we say it in the hallowed halls of academia, what he does is useful. Because frankly a program manager sitting in the BRAC Microfinance office in Kiboga doesn’t have much time to read up on Maslow’s grand hierarchy of needs to analyze human motivation. He’s got $100 and he needs to decide to what to spend it on, soon.

And the consequences of this choice aren’t trivial. That $100 may not come again. Misspending program money isn’t just wasteful and inefficient; in development it’s people’s lives that are falling between the cracks. It’s a young girl—perhaps the next Leymah Gbowee (Nobel Prize-winning Liberian peace activist)—who never goes to school because her father wasn’t motivated enough to stay with a microfinance program. It’s her potential which is squandered when we fail. As excited as we get by the latest technology in development—mobile apps, vaccinations, or GIS tablets—fundamentally the biggest challenge we face in development is still executing well with the money and resources we have. We can, and we must, perform better. So when given $100 we have to think very carefully about the best way to spend it. We can guess and take a gamble with that girl’s future, or we can put our theories to the test. Researchers like Munshi bhai are taking the step between theory and action to do exactly that.