Many years of focus on schooling

Pratham first started its work in the slums of Mumbai a little over two decades ago. At the time, one of our main objectives was to bring children to school and to encourage them to stay in school. We were no different from others, in government and outside, in our belief that achieving universal schooling should be the immediate and high priority goal. This was also around the time that the MDGs and EFAs were taking shape. These global guidelines also influenced the development of many national policies. Children not in school were visible. Parents and practitioners, policymakers and the public, all worked to reduce and eliminate the problem of children not going to school.

In our early work in Mumbai as well as in other urban slums and rural communities around India, we began to feel a different and less visible problem. Everywhere we found many children who despite being in school for several years were struggling to cope with school work. A significant proportion did not seem to have acquired foundational skills. It was hard to exactly pin point the problem, but everyone was uneasy. Teachers were frustrated. Parents were disappointed. Each blamed the other. Children often lost interest in what was going on in the classroom.

The main challenge seemed to be that children were in school, but many were not learning. Even if they were learning, they were not able to keep pace with what was needed for grade-level curricular requirements. Teaching from the textbook, as is customarily done in Indian schools, was leaving more and more children behind. But unlike the problem of not being in school which was visible, the issue of not learning was relatively invisible. Furthermore, given the widespread belief that schooling was synonymous with learning[1], no one was even looking out for such difficulties.

Making the problem of learning visible

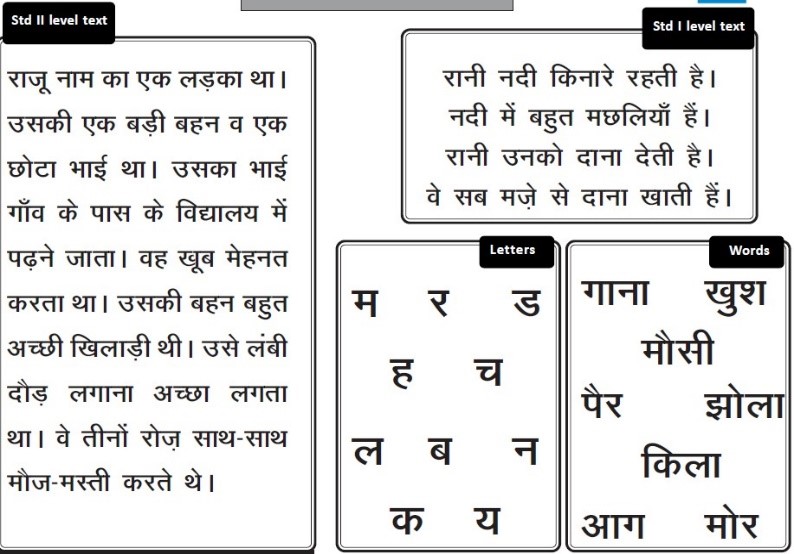

We began to slowly unpack and systematically understand what lay at the core of this issue. What was getting in the way? How to tackle the problem? In working with primary school children, especially those who were already in grade 3 or 4, we realised that without learning to read, a child simply cannot move ahead. In this process we developed a simple tool to assess children’s reading. The tool was used one-on-one with a child, and within a few minutes the assessment gave a good sense of what the child could do and where the child was struggling. For a teacher, it was easy to use. It helped her understand not only where individual children stood, but also the spread of reading levels among the children in her class. It also gave her immediate inputs for what she needed to do and for whom. For parents, many of whom were not very educated, it demystified what “learning” meant and showed them what needed to be done. The highest level of the tool was a “story” at second grade-level. As the first step to developing reading skills, being able to read (and of course understand) the “story” was the goal of the reading programmes that were put in place.[2]

In doing the assessment, the key importance of reading became clear and visible.[3] The business of “learning” had seemed complex and opaque, but the simple tool helped in a manageable way, to lay out, the problem and the possible pathways to the solution. A similar tool and process was developed for arithmetic that focused on the knowledge of numbers and the ability to do basic operations.

Simple assessment to direct action

For the last 15 years, we have used these reading and arithmetic tools as the first step in our instructional work. We have used them to prepare ‘village report cards’, both to help people understand the status of schooling and learning in their village, and to mobilise and train village volunteers to teach children. We have used these tools in schools to create ‘school report cards’ to track progress of children and help teachers initiate activities for ‘learning to read’. Early recognition and identification of a problem leads to timely solutions.

From 2005 to 2016, the simple assessment was also used in an annual nation-wide, now well known, exercise called ASER – Annual Status of Education Report. In this annual household survey, a representative sample of children from every rural district in India is asked to read, recognise numbers, and do simple operations. The survey generates estimates at district, state and national levels for basic reading and arithmetic. It is perhaps the largest household-based annual generation of data on basic learning anywhere in the developing world. Other countries have adapted and transplanted this model in their own countries. Today, there is well established ASER in Pakistan, a similar effort called Uwezo in Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda; Jangandoo in Senegal; Bekungo in Mali, MIA in Mexico. Beginnings of such efforts are visible in Bangladesh and Nepal, and in Nigeria, Mozambique and Ghana. The need to recognise and solve children’s learning problems early in primary school years is clearly something that many others countries have also realised as important.[4]

Time to rethink and rework assessment

For decades, measurement in school systems, in countries like India, have been focused on inputs, infrastructure and provisioning. As we were building large numbers of schools, recruiting hundreds of teachers, printing thousands of textbooks, and enrolling millions of children, we needed to count and measure progress in a particular way. We had not developed our own systems for measuring learning other than examinations at terminal points in the education system.

Recently, as children’s learning has moved to the centre stage and gained importance as a development goal, we are leaning on student assessment models, metrics and methods that have evolved over time in developed countries. Not surprisingly, such measurements respond to the needs and capabilities of the contexts in which they originated. In this regard, developed countries are different in many significant ways from developing countries. For example, many western countries have had universal enrolment for several decades. Child populations and age-grade distributions have stabilised over time. All schools are registered in national records. Also, in these countries, most parents are educated, and thus have a better understanding of what it takes to progress through school. In these education systems, assessment is usually an integral part of the overall teaching-learning framework that guides instruction. All of these factors ensure that data on students’ progress feeds into decisions and plans for improvements in the education system. But is that the case in our context?

Through Pratham’s instructional work and in the large-scale experiences from ASER, we have learned some straightforward and sturdy lessons. First, if a child cannot read, there is no point in giving him or her, a pencil-and-paper test. In countries where many children are still struggling to read, the only way to understand what they can do is by sitting with each child, one-on-one, listening to them as they try different tasks. Second, the effort to understand each child can also be linked to developing an understanding of the aggregate (whether at the class level, school level or higher). If the assessment is designed appropriately, it can quite easily lead to action. Third, the more people that “feel” and “see” the problem, the higher are the chances that the problem will be solved.

After having done ASER for 11 years, we believe our form of assessment has had a significant influence on policy makers, both in India and overseas. Learning outcomes are now central to all discussions on elementary education. Even SDG 4.1 articulates it clearly. [5]

Time has also come to rethink assessment. Will more assessment solve the problem of non-learning? As India and other countries experiment with measuring student outcomes, we need to consider how much of the available assessment approaches and models are appropriate, relevant or useful for our current context. Should we modify or adapt existing paradigms? Or do we need to develop indigenous models that suit our realities? We need indicators, tasks and processes that better serve our current needs and realities. Our assessment practices need to be aligned to our current capabilities for measurement. Assessment is not merely an exercise of data collection for academic reasons. It needs analysis, communication and translation into action. It is time to ensure that assessment can be understood by teachers and parents, and by planners and policymakers. And that whatever assessment we do becomes an integral part of ongoing teaching-learning efforts that help children learn. [6]

[1] In fact, in many languages the common word for education is almost the same as that for learning. For example, in Hindi, “padhai”; in Bangla “lekha-poda”.

[2] For a longer discussion of how assessment can feed into action see http://www.pratham.org/templates/pratham/images/Assessment&Data-in-TaRL-19_9_2017.pdf

[3]https://www.brookings.edu/blog/education-plus-development/2014/05/22/from-invisible-to-visible-being-able-to-see-the-crisis-in-learning/

[4] See PAL (People’s Action for Learning) network for details of all of these citizen led assessments worldwide. Palnetwork.org

[5]http://indicators.report/targets/4-1/

[6] For some other publications on the same theme, see:

http://www.riseprogramme.org/content/building-movement-assessment-action

https://ssir.org/articles/entry/when_schooling_doesnt_mean_learning

http://www.acer.edu.au/files/Research-Conference-Proceedings-2015.pdf

|

Dr Rukmini Banerji CEO of Pratham Education Foundation |

|

Ranajit Bhattacharyya General Manager and Head of Communications at ASER Centre |