This spring, Daniel Ng was the winner of BRAC’s first Facebook Innovation Contest . He visited us in August to work with the Social Innovation Lab on advancing his idea. His reflections are below. You can watch his submission video and final presentation on the BRAC youtube channel.

Earlier this year, BRAC ran a competition through Facebook to find innovative ideas with the potential to “change the world to a more inclusive and equitable place”. I sent in a proposal to build community playgrounds in Bangladesh, one next to each of BRAC’s primary schools, with the goal being to create safe, accessible places for underprivileged children to play. Even now, I can’t believe BRAC chose my idea. A disbelief not because of any weakened conviction about the importance of protecting play, but because of wondering, Why me? What does the world’s largest NGO want with me, a first-year undergrad from Virginia who is clearly not Bangladeshi? Whatever the reason, I packed my bags, flew to Bangladesh, and walked into BRAC’s 20-story beehive of an office with nothing but good intentions and high hopes that BRAC would implement my plan soon. Obviously, I still had a lot to learn.

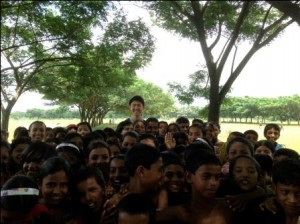

Over the next one and a half weeks I worked closely with BRAC’s Social Innovation Lab to better understand how my idea could fit into BRAC programming, especially its Education Program. One of my most memorable and humbling experiences during that time was when I got the opportunity to “visit the field,” so to speak. The “field” turned out to be an urban region called Kumkumari, Savar located about 30 km northwest of Dhaka city. I was taken there to observe a pilot project BRAC is currently running to promote outdoor recreation. Since the beginning of 2012, BRAC has been piloting a project to incorporate outdoor play activities into its primary education program. Every Thursday after class, BRAC teachers lead their students to a nearby field to engage in 1 hour of semi-structured outdoor play. So while not to the rural, agricultural area I had in mind, my “field visit” ended up being exactly that, a visit to a field.

Speaking with participants of the pilot program, though, I quickly began to realize just how inappropriate and unfeasible my playground idea really was. First of all none of the students, parents, and teacher I interviewed knew what a “playground” was. The concept of a playground as a space filled with equipment to play on was as foreign to them as I was. To the community members of Kumkumari, a “playground” is any field where children can run around and play games like football orkanamachi (a blindfolded version of tag). Building a Western playground in the community would not only be insensitive to their culture, but also irrelevant to their existing needs.

There was also a lack of space. My original plan was to have a playground built next to each of BRAC’s primary schools, but after visiting Savar, this no longer seems possible. To construct a playground next to the school in Kumkumari would mean making room for it first, demolishing any one of the important structures that already exist, from the school latrine to the communal water tank. It became clear to me that without major modifications, my playground idea most definitely would not “change the world to a more inclusive and equitable place.”

I should have listened first. More than just a polite gesture, listening communicates respect, a valuing of the other person’s ideas, thoughts, and being. Treating a community as merely a testing ground to pilot an innovation, especially one developed exclusive of community members, does not convey respect. Instead, communities should be seen as a source of innovation, one of the first places to look for new ideas that have the potential to make the world a “more inclusive and equitable place.” If I had not taken the time to listen to the community members of Kumkumari, I would never have found out that they currently lack medical supplies in their schools and on their play field. Ingenuity can happen anywhere, but some of the most beneficial ideas can only come from within a community itself.

Listening to the community also helps identify existing needs, which in turn helps gauge the usefulness of a particular innovation. Innovation demands putting the needs of the beneficiary first; however, for the longest time I had considered the playground idea my project, something I owned and controlled. That was probably the first indication that my idea wouldn’t work too well. The playground concept isn’t about me; it’s about the children of Bangladesh and ensuring they have a safe space to play.

As you can imagine, a major overhaul of the playground idea occurred as a result of my trip to Savar, but I don’t regret it. I am actually relieved BRAC didn’t implement any playgrounds this summer because while I still believe protecting play is important, my way probably would have caused more harm than good. Here are some of my recommendations for BRAC now:

• Deliver first aid training and supplies to each of BRAC’s primary schools

• Improve BRAC’s current pilot project by adding more structure to the outdoor play so that its benefits are measurable

• Create space for play within BRAC by sensitizing program directors about the importance of play as a tool for development

I came to BRAC with high hopes and good intentions. Fortunately, my hopes haven’t disappeared, just been redirected. Now I have high expectations that BRAC will continue what it has been doing so well for the past 40 years: listening to the people they serve. As for my good intentions, they are still there too, but I’ve learned to take them with a grain of salt. I realize now that good intentions are not enough and having them is not sufficient justification to go around “developing” other people’s lives. Thanks BRAC for the healthy reminder.